-------------

-------------

----------------------------------

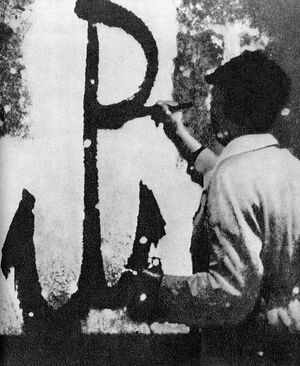

The symbol of the Polish resistance being painted on a wall in German-occupied Poland

Today’s Comic: Mae West: “I generally avoid temptation unless I can't resist it.”

Today’s Insult: “Some white supremacists are now upset because they’re taking DNA tests and discovering they’re part black. And you know who’s even more upset? Their black ancestors. - President Trump said that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s choice to not attack Guam was a “wise and well-reasoned decision.” Trump said, “Someday I’m gonna make one of those.” - In a tweet this morning, President Trump called Confederate statues “beautiful.” People were shocked because it’s the first time Trump has complimented anything that’s over 40 years old. - President Trump tweeted this morning that he’s “sad” over the removal of our “beautiful statues.” Of course, Trump may just be sticking up for his fellow bronze-colored symbols of hate. - The American Cancer Society has decided not to host its charity event at Trump’s resort, Mar-a-Lago. You know it’s not a good sign for Trump when he’s considered too toxic for cancer. - Hillary Clinton is coming out with a book called “What Happened.” Out of habit, Bill Clinton immediately came out with his own book called ‘Baby, I Can Explain’.” –Conan O’Brian

Today’s Wisdom: “But without Adolf Hitler, who was possessed of a demonic personality, a granite will, uncanny instincts, a cold ruthlessness, a remarkable intellect, a soaring imagination and—until the end, when, drunk with power and success, he overreached himself—an amazing capacity to size up people and situations, there almost certainly would never have been a Third Reich.” -William L. Shirer

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies

Note: Images may or may not accurately represent the item adjacent to them. Also, please note that there is much, much, MUCH more detail available-and many, many, MANY more items as well-every day on the linked What Happened Today page. Disclaimer: The selected Quotes, Jokes and Cartoons may or may not represent the views of the compiler of these daily posts. If they give you something to think about, they will have accomplished their task. Levi Bookin, Copy Editor, in particular bears no responsibility for any of them. He does, however, do a truly admirable job on the linked Daily pages, which everyone should peruse on a daily basis. It is WELL worth the small effort required. The Trick is to Click-> August 22 & August 23 & August 24 & August 25 & August 26 & August 27 & August 28 & August 29 & August 30 & August 31

From Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth, by Gitta Sereny(*****): Jean Michel, a French slave laborer at Dora (Speer met him in Essen in 1947, when he and Wernher von Braun were called as witnesses at the war crimes trial of Dora guards), was born in Paris in 1906. He was thus one year younger than Speer, thirty-eight to Speer's thirty-nine in 1943, when Speer came to inspect Dora.

"It was a cold day in December when I went there," Speer told me. "I was entirely unprepared; it was the worst place I have ever seen."

It was the morning after our conversation about October 6. Again Margret had gone skiing; again we sat at that comfortable kitchen table; again, immediately and impossible to fake, his face went pale; again he covered his eyes for a moment with his hand. "Even now when I think of it," he said, "I feel ill." The prisoners, he said, lived in the caves with the rockets; it was freezing cold, humid. Jean Michel described it in his book, Dora:

"The missile slaves . . . from France, Belgium, Holland, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Russia, Poland and Germany... toiled eighteen hours a day . . . for many weeks without tools, just with their bare hands . . . ammonia dust burnt their lungs . . . they slept in the tunnels in cavities which were hollowed out: 1,024 prisoners in hollows on four levels which stretched for 100 yards..."

"I was outraged," Speer told me. "I demanded to see the sanitary provisions...."

From Dora: "No heat, no ventilation, not the smallest pail to wash in: death touched us with the cold, the sensation of choking, the filth that impregnated us. . . . The latrines were barrels cut in half with planks laid across. They stood at each exit from the rows of sleeping cubicles." One of the SS guards' favorite jokes, Michel wrote, was to watch the slaves sit on the plank, laugh and push them into the barrel. "We all had dysentery. They laughed and laughed when we tried to get up and out of the shit..."

"I walked past these men and tried to meet their eyes," Speer said, despair in his voice. "They wouldn't look at me; they ripped off their prisoners' caps and stood at attention until we passed." From Dora: "The deportees saw daylight only once a week at the Sunday roll call. The cubicles were permanently occupied, the day team following the night team and then vice versa . . . no drinkable water . . . you lapped up liquid and mud as soon as the SS had their backs turned...."

"I demanded to be shown their midday meal," Speer said. "I tried it; it was an inedible mess." After the inspection was over he found out that thousands had already died. "I saw dead men . . . they couldn't hide the truth," he said. "And those who were still alive were skeletons." He had never been so horrified in his life, he said. "I ordered the immediate building of a barracks camp outside, and there and then signed the papers for the necessary materials.. . . "

Michel in Dora:

"It was not until March 1944 that the barracks were completed. At Dora, the work was as terrible as ever, but we could at least leave the tunnel for the six hours of rest allowed..."

Eventually, thirty-one sub-camps surrounded the Dora complex deep under these mountains, Jean Michel wrote, and added bitterly that no one could convince him that General Walter Dornberger (who after the war became a missile consultant to American aviation until he peacefully retired to Buffalo, New York) and his Peenemünde team of scientists, above all Wernher von Braun, who equally harvested financial and scientific glories in the United States, did not know who built their rockets and under what conditions. All these men, he says, collaborated with historians and writers after the war and indeed wrote books and papers themselves. "The word 'Dora,' " he wrote, "does not appear in any of those writings." It was, he says, as if that hell on earth had never been. Sixty thousand men were deported to Dora; thirty thousand of them died.

When I asked Speer what he had felt at Dora, it was the only time he admitted feeling something for the slave workers. "I was appalled," he said. "Yes," he repeated, almost as if in retrospect he was surprised at having given way to feeling, "Yes, there I was appalled."

From The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000, by Paul M. Kennedy(*****): The real point about the Prussian system was not that it was free of errors, but that the general staff carefully studied its past mistakes and readjusted training, organization, and weapons accordingly. When the weakness of its artillery was demonstrated in 1866, the Prussian army swiftly turned to the new Krupp breechloader which was going to be so impressive in 1870. When delays occurred in the railway supply arrangements, a new organization was established to improve matters. Finally, Moltke's emphasis upon the deployment of several full armies which could operate independently yet also come to one another's aid meant that even if one such force was badly mauled in detail—as actually occurred in both the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian wars—the overall campaign was not ruined.

It was therefore a combination of factors which gave the Prussians the swift victory over the Austrians in the summer of 1866 that few observers had anticipated. Although Hanover, Saxony, and other northern German states joined the Habsburg side, Bismarck's diplomacy had ensured that none of the Great Powers would intervene in the initial stages of the struggle; and this in turn gave Moltke the opportunity to dispatch three armies through separate mountain routes to converge on the Bohemian plain and assault the Austrians at Sadowa (Koeniggratz). In retrospect, the outcome seems all too predictable.

Over one-quarter of the Habsburg forces were needed in Italy (where they were victorious); and the Prussian recruitment system meant that despite Prussia's population being less than half that of its various foes, Moltke could deploy almost as many front-line troops.

The Habsburg army had been underfinanced, had no real staff system, and was ineptly led by Benedek; and however bravely individual units fought, they were slaughtered in open clashes by the far superior Prussian rifles. By October 1866, the Habsburgs had been forced to cede Venetia and to withdraw from any interest in Germany—which was by then well on its way to being reorganized under Bismarck's North German Federation. The "struggle for mastery in Germany" was almost complete; but the clash over who was supreme in western Europe, Prussia or an increasingly nervous and suspicious France, had been brought much closer, and by the late 1860s each side was calculating its chances.

Ostensibly, France still appeared the stronger. Its population was much larger than Prussia's (although the total number of German speakers in Europe was greater). The French army had gained experience in the Crimea, Italy, and overseas. It possessed the best rifle in the world, the Chassepot, which far outranged the Prussian needlegun; and it had a new secret weapon, the mitrailleuse, a machine gun which could fire 150 rounds a minute. Its navy was far superior; and help was expected from Austria-Hungary and Italy. When the time came in July 1870 to chastise the Prussians for their effrontery (i.e., Bismarck's devious diplomacy over the future of Luxembourg, and over a possible Hohenzollern candidate to the Spanish throne), few Frenchmen had doubts about the outcome.

The magnitude and swiftness of the French collapse—by September 4 its battered army had surrendered at Sedan, Napoleon III was a prisoner, and the imperial regime had been overthrown in Paris—was a devastating blow to such rosy assumptions. As it turned out, neither Austria-Hungary nor Italy came to France's aid, and French sea power proved totally ineffective. All therefore had depended upon the rival armies, and here the Prussians proved indisputably superior. Although both sides used their railway networks to dispatch large forces to the frontier, the French mobilization was much less efficient. Called-up reservists had to catch up with their regiments, which had already gone to the front. Artillery batteries were scattered all over France, and could not be easily concentrated. By contrast, within fifteen days of the declaration of war, three German armies (of well over 300,000 men) were advancing into the Saarland and Alsace. The Chassepot rifle's advantage was all too frequently neutralized by the Prussian tactic of pushing forward their mobile, quick-firing artillery. The mitrailleuse was kept in the rear, and never employed effectively. Marshal Bazaine's lethargy and ineptness were indescribable, and Napoleon himself was little better. By contrast, while individual Prussian units blundered and suffered heavy losses in "the fog of war," Moltke's distant supervision of the various armies and his willingness to rearrange his plans to exploit unexpected circumstances kept up the momentum of the invasion until the French cracked. Although republican forces were to maintain a resistance for another few months, the German grip around Paris and upon northeastern France inexorably tightened; the fruitless counterattacks of the Army of the Loire and the irritations offered by francs-tireurs could not conceal the fact that France had been smashed as an independent Great Power.

The triumph of Prussia-Germany was, quite clearly, a triumph of its military system; but, as Michael Howard acutely notes, "the military system of a nation is not an independent section of the social system but an aspect of it in its entirety." Behind the sweeping advances of the German columns and the controlled orchestration of the general staff there lay a nation much better equipped and prepared for the conditions of modern warfare than any other in Europe. In 1870, the German states combined already possessed a larger population than France, and only disunity had disguised that fact. Germany had more miles of railway lines, better arranged for military purposes. Its gross national product and its iron and steel production were just then overtaking the French totals. Its coal production was two and a half times as great, and its consumption from modern energy sources was 50 percent larger. The Industrial Revolution in Germany was creating many more large-scale firms, such as the Krupp steel and armaments combine, which gave the Prusso-German state both military and industrial muscle. The army's short-service system was offensive to liberals inside and outside the country—and criticism of "Prussian militarism" was widespread in these years—but it mobilized the manpower of the nation for warlike purposes more effectively than the laissez-faire west or the backward, agrarian east. And behind all this was a people possessing a far higher level of primary and technical education, an unrivaled university and scientific establishment, and chemical laboratories and research institutes without an equal.

Europe, to repeat the quip of the day, had lost a mistress and gained a master.

From While England Slept, (a 1939 compilation of speeches) by Winston S. Churchill(***) (This excerpt is from prescient remarks delivered in the House on April 13, 1933): I have heard, as everyone has of late years, a great deal of condemnation of the treaties of peace, of the Treaties of Versailles and of Trianon. I believe that that denunciation has been very much exaggerated, and in its effect harmful. These treaties, at any rate, were founded upon the strongest principle alive in the world today, the principle of nationalism, or, as President Wilson called it, self-determination. The principle of self-determination or of nationalism was applied to all the defeated Powers over the whole area of Middle and Eastern Europe. Europe today corresponds to its ethnological groupings as it has never corresponded before. You may think that nationalism has been excessively manifested in modern times. That may well be so. It may well be that it has a dangerous side, but we must not fail to recognize that it is the strongest force now at work.

I remember, many years ago, hearing the late Mr. Tim Healy reply to a question that he put to himself, "What is nationalism?" and he said, "Something that men will die for." There is the foundation upon which we must examine the state of Europe and by which we should be guided in picking our way through its very serious dangers. Of course, in applying this principle of nationalism to the defeated States after the War it was inevitable that mistakes and some injustices should occur. There are places where the populations are inextricably intermingled. There are some countries where an island of one race is surrounded by an area inhabited by another. There were all kinds of anomalies, and it would have defied the wit of men to make an absolutely perfect solution.

In fact, no complete solution on ethnographical lines would have been possible unless you had done what was done in the case of Greece and Turkey—that is, the physical disentangling of the population, the sending of the Turks back to Turkey and of the Greeks back to Greece—a practical impossibility.

I recognize the anomalies and I recognize the injustices, but they are only a tiny proportion of the great work of consolidation and appeasement which has been achieved and is represented by the Treaties that ended the War. The nationalities and races of which Europe is composed have never rested so securely in their beds in accordance with their heart's desire. It would be a blessed thing if we could mitigate these anomalies and grievances, but we can only do that if and when there has been established a strong confidence that the Treaties themselves are not going to be deranged. So long as the Treaties are in any way challenged as a whole it will be impossible to procure a patient consideration for the redress of the anomalies. The more you wish to remove the anomalies and grievances the more you should emphasize respect for the Treaties.

It should be the first rule of British foreign policy to emphasize respect for these great Treaties, and to make those nations whose national existence depends upon and arises from the Treaties feel that no challenge is leveled at their security. Instead of that, for a good many years a lot of vague and general abuse has been leveled at the Treaties with the result that these powerful States, comprising enormous numbers of citizens—the Little Entente and Poland together represent 80,000,000 strongly armed—have felt that their position has been challenged and endangered by the movement to alter the Treaties. In consequence, you do not get the consideration which in other circumstances you might get for the undoubted improvements which are required in various directions . . . .

New discord has arisen in Europe of late years from the fact that Germany is not satisfied with the result of the late War. I have indicated several times that Germany got off lightly after the Great War. I know that that is not always a fashionable opinion, but the facts repudiate the idea that a Carthaginian peace was in fact imposed upon Germany. No division was made of the great masses of the German people. No portion of Germany inhabited by Germans was detached, except where there was the difficulty of disentangling the population of the Silesian border. No attempt was made to divide Germany as between the northern and southern portions, which might well have tempted the conquerors at that time. No State was carved out of Germany. She underwent no serious territorial loss, except the loss of Alsace and Lorraine, which she herself had seized only fifty years before . . . .

On the other hand, when we think of what would have happened to us, to France or to Belgium, if the Germans had won; when we think of the terms which they exacted from Rumania, or of the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk; when we remember that up to a few months from the end of the War German authorities refused to consider that Belgium could ever be liberated, but said that she should be kept in thrall for military purposes forever, I do not think that we need break our hearts in deploring the treatment that Germany is receiving now . . . .

I am not going to use harsh words about Germany and about the conditions there. I am addressing myself to the problem in a severely practical manner. Nevertheless, one of the things which we were told after the Great War would be a security for us was that Germany would be a democracy with Parliamentary institutions. All that has been swept away. You have dictatorship—most grim dictatorship. You have militarism and appeals to every form of fighting spirit, from the reintroduction of dueling in the colleges to the Minister of Education advising the plentiful use of the cane in the elementary schools. You have these martial or pugnacious manifestations, and also this persecution of the Jews, of which so many Members have spoken and which distresses everyone who feels that men and women have a right to live in the world where they are born, and have a right to pursue a livelihood which has hitherto been guaranteed them under the public laws of the land of their birth . . . .

I cannot help rejoicing that the Germans have not got the heavy cannon, the thousands of military aeroplanes and the tanks of various sizes for which they have been pressing in order that their status may be equal to that of other countries.

From The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler, by Robert Payne(***): The weeks that followed the assassination attempt were disastrous for the German Army. On July 31, 1944, the allies made their great breakthrough at Avranches. On August 2 Turkey broke off relations with Germany. On August 15 the allies landed on the French Mediterranean coast, and four days later vast numbers of German troops were encircled at Falaise in Normandy. August 20 marked the beginning of the Soviet breakthrough on the front of Army Group South Ukraine, and three days later there was a revolution in Rumania, which immediately declared war on Germany. Hitler had attached enormous value to the Rumanian oil fields, and now they were lost to Germany. Bulgaria revolted a few hours later. On August 25 the allies marched into Paris.

The effect of these reverses on Hitler's constitution was much greater than the damage he suffered when the conference room blew up. He became listless and apathetic, the stomach cramps became worse, and he spent three weeks in bed. To Frau Junge, one of his secretaries, he said, "If these stomach spasms continue, my life will have no sense. In that case I will have no hesitation in putting an end to my life." In late August and September, 1944, he was in worse physical shape than at any time except when he was suffering from starvation in Vienna and when he was lying blind in the hospital at Pasewalk at the end of World War I. Nevertheless, he missed very few military briefings and continued to give orders. He entered the map room with glassy eyes, bent and shuffling. His chair was pushed forward for him, and he slumped down with his head shrunken into his shoulders. With the front crumbling in all directions, he would suddenly look up sharply and say: "Anyone who speaks to me of peace without victory will lose his head, no matter who he is or what his position!" What appeared to fascinate him more than anything else was the hunt for the conspirators, and he read the stream of reports sent by Himmler with special avidity. More and more he came to suspect his generals, and he was as viperish as ever when they asked permission to withdraw.

Self-pity was not one of his more notable traits, but in these months of defeat he gave full vent to it, and sometimes he would discuss even with his generals the possibility that he might commit suicide. On August 31, 1944, he told his generals that during the whole course of the war he had seen no films, attended no theatrical performances, lived a life of perfect dedication, never for a moment derived any pleasure from the war, and now at last he was prepared to end it all. The monologue in which he describes his own miseries has survived in a rather fragmentary form, but the passages in which he hints at suicide are quite clear. He said:

"That this war has never given me any pleasure should be obvious to everyone. For five years I have been cut off from the rest of the world. I have never been able to visit the theater or hear a concert or see a film [Note: Hitler is being less than honest in this case. While he did indeed avoid going to the theater and the Opera during the War, he nevertheless viewed many films-his taste was for light Hollywood comedy's, musicals, and Disney cartoons-in his own private viewing room surrounded by his crony's.]. I live only for one purpose, to lead this fight: for without an iron will, this struggle can never be won. I accuse the General Staff of weakening the front-line officers, who came here, and instead of exhibiting an iron will these officers of the General Staff were full of pessimism when they went to the front . . . .

"If necessary we shall fight on the Rhine. Under all circumstances we shall continue to fight until, as Frederick the Great said, one of our damned enemies gets too tired to fight any more, and we'll go on fighting until we achieve a peace that will secure the life of the German nation for the next fifty or a hundred years, one that does not bring our honor for the second time into disrepute, as happened in 1918. This time I'm not going to keep my mouth shut. Then no one said anything.

"Fate might have run a different course. If my life had ended, then I daresay that for me personally it would have been a release from worry, sleepless nights, and intense nervous suffering. A split second, and then one is free of it all, and there is rest and eternal peace. But I am grateful to fate for letting me live."

These mournful thoughts arose from the contemplation of the suicide of Field Marshal von Kluge, who had succeeded Rundstedt as commander-in-chief, West. Kluge held his command for only a few weeks. On a visit to the front he was cut off from his headquarters by a heavy bombardment. For a whole day he was out of touch with his army and with Hitler, who became wildly suspicious and believed that he was in secret communication with the British. There was no truth in the suspicions.

Kluge returned to his headquarters and learned that he had been superseded by Field Marshal Walter Model and was under orders to report to Hitler. On a flight from Paris to Metz he took poison, leaving a letter for Hitler. "You have fought a great and honorable fight," he wrote. "Now show yourself great enough to put a necessary end to a struggle which is now hopeless."

The letter infuriated Hitler, but what infuriated him even more was that Kluge, by taking poison, had escaped his just punishment.

[Note: Renowned author and historian Pierre Stephen Robert Payne's Hitler biography is a very good read indeed, and his analysis of his subject is profound and succinct. However, the work itself is flawed and should be perused cautiously. Payne utilizes a number of spurious sources as if they were gospel; Hitler in Liverpool, etc.. These sources were accepted by consensus as genuine at the time of the writing, but their inclusion in the book reduces its usefulness. Still, if one ignores the Liverpool chapter, as well as some Vienna details, Payne is well worth reading.]

From Hitler's Foreign Policy 1933-1939: The Road to World War II, by Gerhard L. Weinberg(****): If Ciano was certain that a general war was imminent and that Italy should stay out, the Duce was wavering between his bellicose inclinations and his fear of appearing to betray his German ally on the one hand and his recognition of Italian unpreparedness, exhaustion of resources in fighting for four years in Ethiopia and Spain, and opposition to war on the part of almost all his advisers on the other. He authorized Ciano to work on a compromise formula under which Germany would receive Danzig as a down payment and other concessions in some sort of conference that, like the Munich one, he would grace with his presence; but he would soon discover that neither side was interested. The English did not trust Hitler to keep his word after his recent breach of the Munich agreement and did not in any case want to urge concessions on Poland in the face of German threats, while a peaceful settlement was the last thing Hitler wanted.

The different view Italy took of the situation and the possibility that in the face of Western determination Italy might abstain from war were known in London and Paris, and during the days after 23 August every effort was made to encourage this development. In line with a suggestion of French Prime Minister Daladier, President Roosevelt also appealed to the Italians to use their influence for the maintenance of peace. With the defeat of the administration's effort to have the neutrality law amended, neither this appeal nor a subsequent one to Hitler could have much effect; but in addition to focusing public attention on Germany's determination to start a war, this American initiative did serve to remind the Italian government of the dangerous implications of a wider conflict.

Into this situation came von Ribbentrop's telephone call of the night of 24-25 August, as a result of which Ciano first succeeded and then failed to secure a decision by Mussolini to stay out of the coming war for the time being. The "strong man" of Italy swung back and forth repeatedly; Hider's letter of 25 August reached him during the hours of alternating moods. Now he had to decide on an unequivocal answer. He could promise Germany Italian assistance under circumstances Italy had not foreseen and Germany had kept secret until the last moment—even now the Germans did not reveal that war was to start fourteen hours after von Mackensen delivered Hitler's letter. Or he could follow the advice of Ciano, the king, and many others by telling Hitler that for the time being, Italy would have to stay out. Ciano persuaded the Duce to follow the latter course; and with a heavy heart Mussolini wrote to Hitler, explaining that in view of the war coming much earlier than had been expected when the Pact of Steel was signed, Italy could not join until she had the equipment and the raw materials she needed. The most important single factor leading to the Italian decision had been the certainty of both Mussolini and Ciano that Britain and France would fight alongside Poland; at 5:30 p.m. the Italian answer was phoned to Attolico for transmittal to the impatient Germans. As soon as Hider had finished his conversation with Coulondre, he learned of the Italian reply. In view of his anticipation of Mussolini's full support, Hitler was stunned. But this was not the only bad news: practically simultaneously with Mussolini's letter Hitler received the news that England had signed an alliance with Poland.

This symbol of the determination of England, of which the Italians had been convinced much earlier, finally suggested to Hider that his calculations were not as accurate as he had thought. The signature of the Anglo-Polish alliance at this moment was partly a deliberate answer to the German government's possible doubts about England's position and partly a coincidental matter of timing. The discussions for a formal Anglo-Polish pact had been continuing for some time, with much of the delay due to the desire of London so to phrase the treaty as to make it fit with the anticipated treaty of England with the Soviet Union. The Anglo-Pobsh was seen as subordinate to the Anglo-Soviet treaty text,45 and as the negotiations for the latter dragged on endlessly through the summer, those for the former were practically suspended. Now that it was obvious there would be no agreement with the Soviet Union at all, quick steps were taken to finalize the text of the Anglo-Polish one. It was ready for signature on 25 August, the final stages having been hurried because of the obvious urgency of the international situation.48 Public announcement of the signature at 5:35 p.m. on 25 August thus reached Hitler after he had given Henderson the alliance offer to take to England and had already issued the final order to attack Poland on the next day.

Faced by the two unpleasant surprises, Italian defection and British resolution, both of which were surprises only because he had himself miscalculated, Hitler checked with the military to see whether the attack could still be called off. When the high command of the army responded that they thought this was possible, Hitler ordered the troops back to their stations around 7:30 p.m. Almost all the units could be recalled and the naval action at Danzig could also be stopped in time, but a number of incidents and preparatory steps gave many the clear indication that war had indeed been scheduled for 26 August.

The discussion of the outbreak of World War II has recorded the recall of the order to attack Poland without fully taking into account the implications of the circumstances for an understanding of Hitler's actions in the final days of peace. It must be noted that Hitler had first asked the military whether a recall was even possible, a question that obviously implies his being prepared for the answer that it was already too late; whenever Hitler was certain in his own mind what ought to be done, he told rather than asked his generals. Hitler's decision to go to war, thus, was a real one, not a diplomatic bluff, and he was quite prepared to stick with it in spite of the two pieces of bad news he had received, if the military situation demanded proceeding with it. Since the army's leaders thought they could halt the German war machine in time, however, Hitler had a few days for further diplomatic moves before striking.

When the Fuehrer called off the attack on 25 August, he was by no means abandoning his intention of starting a war against Poland. He had originally called for the army to be ready by 1 September, had then moved up the date to 26 August because he wanted to start as early as possible; he explained to the high command of the army that in his opinion the latest feasible date on which they could start would be 2 September. After the latter date, the previously discussed weather problems would in Hiter's opinion prevent victory in the one brief campaign that he wished to wage against Poland.

When calling off the operation scheduled for 26 August, therefore, Hitler still felt he had some leeway before the whole project would have had to be scrapped for 1939. As will be seen, he did not in the end use all the days he believed he had available to him but instead ordered the attack when by his own reckoning he could have safely postponed war for one more day. This matter will be discussed later, but first the way Hitler used the days of postponement will be examined briefly.

Hitler postponed the attack only because he had a few days to try to make his original diplomatic strategy work. As General Halder, the army chief of staff, learned on the 26th, Hitler had deferred action in the hope of still isolating Poland by separating Britain and Poland.52 The alliance offer would, he hoped, arouse sufficient doubts in London or lead the English government so to explore the project that in the process Poland would be abandoned to her fate. Hitler still preferred to fight his wars with Poland and with the Western Powers in sequence rather than at the same time.53 In a secret speech at the chancellery on 27 August he explained to some of the generals and to members of the Reichstag, who had originally been summoned to hear the war speech Hitler had also postponed, that war was indeed at hand. He was apparently concerned lest any of his associates conclude from what they might have learned about the events of 25 August that there would be no war.

Hitler's negotiating strategy in these days was fairly simple. He checked promptly whether Mussolini's letter declining to join immediately in a war unless Germany provided the needed weapons and war materials was a nominal or a real refusal. He asked what specifically Mussolini wanted, and when he wanted it, only to receive a long list that was partly designed—and looked as if it were designed—to be impossible of fulfillment within any reasonable period of time. As Hitler had explained to Mussolini, he himself was willing to risk war with the West in order to settle accounts with Poland. In the face of the Duce's deep regret over his inability to join in the war, Hitler could only express his acceptance of Italy's position and ask that Rome at least keep up the pretense that Italy would fight because Hitler thought that this would contribute to his effort to keep the Western Powers from intervening. If a general war did break out, he told Mussolini that Germany would win first in the east and then in the west, either in the coming winter or in the following spring.

As for Mussolini, he was unhappy enough about Italy's incapacity to participate in war at that time that he tried to work out new peace plans and conference proposals during the last days of peace. Without reviewing these projects in detail, one could say by way of summary that his idea of starting negotiations by the cession of Danzig as a preliminary concession to Germany was not only unacceptable to the Western Powers and to Poland, but was totally unacceptable to Hitler. From Berlin the Duce was discouraged from expecting any possibility of peace and from thinking that the Germans were at all interested in a negotiated settlement. As Hitler wrote Mussolini on 1 September, he did not want him to try to mediate.

The Italian dictator did not return to a more belligerent position during these days of anxious negotiations as he had from time to time in the period before 25 August. The continued arguments of Ciano, Attolico, and other figures in the Italian government doubtless contributed to this, but it is also reasonable to assume that knowledge of Hitl's alliance offer to England had some part in keeping Mussolini in his less bellicose position. When Hitler had offered to return to the League of Nations in March 1936 right after Italy had left Geneva, there was great resentment in Rome. Now the Italians learned from London, not from their German ally, that Germany was offering to defend the British Empire—presumably against such powers as Italy! As Hitler's concentration on securing his immediate goal of an agreement with Russia had antagonized the Japanese, so now his single-minded absorption on trying to separate England from Poland created difficulties with Italy. In the course of World War II, their aggressive ambitions would bring the three powers together once again, but hardly out of love for each other.

When, partly in response to British and French appeals to restrain Germany and partly in hope of stopping a war from which he would have to abstain, Mussolini tried to halt the spreading conflagration after Germany's attack on Poland, his effort would quickly collapse over the issue of German troops pulling back to the pre-hostilities border. From Germany's point of view, any Italian proposal was of use only for possibly affording a few days of additional diplomatic confusion while the German army advanced so rapidly that the war in the east might look to the West as finished and hence not worth joining. But beyond that tactical objective, Berlin was as uninterested in Italy's peace efforts after as before 1 September. Hider, who had recovered from the surprise of 25 August and continued to have a high regard for the Duce, reassured him on 3 September that any peace would have lasted only a short time, which England and France would have utilized so to strengthen Poland as to make any eastern campaign more time-consuming; now was the best time to fight England and France, and in the final analysis Germany and Italy would have to work and fight together.

From The Meaning of Hitler, by Sebastian Haffner(****): Hitlerism has at least one thing in common with Marxism – the claim to be able to explain the whole of world history from one single point of view. 'The history of all society so far is a history of class struggles', we read in the Communist Manifesto, and analogously in Hitler, 'All events in world history are merely the manifestation of the self-preservation drive of the races'. Such sentences have considerable emotive power. Anyone reading them has the feeling of suddenly seeing the light; what had been confused becomes simple, what had been difficult becomes easy. To those who willingly accept them such statements give an agreeable sense of enlightenment and knowledge, and they moreover arouse a certain furious impatience with those who do not accept them, since in all such words of command there is a ring of ' . . . and anything else is a lie'. This mixture of swaggering superiority and intolerance is found equally among convinced Marxists and convinced Hitlerites.

It is, of course, an error that 'all history' is either this or that. History is a jungle, and no clearing that one cuts into it opens up the whole forest. History has known class struggles and racial clashes, and also conflicts (indeed more frequently) between states, nations, faiths, ideologies, and so on. There is no conceivable human community that might not, in certain circumstances, find itself in conflict with another - and, historically, it is hard to find one which has not at some time been so.

But history - and that is the second error in such dictatorial statements - does not consist solely of fighting. Both nations and classes have lived over much longer periods in peace with one another than at war, and the means by which they achieve this peace are at least as interesting and worthy of historical research as are the factors which, from time to time, lead them into warlike clashes.

One of those means is the state, and it is significant that in Hitler's political system the state plays an entirely subordinate part. Once before, in a totally different context, when we were considering Hider's achievements, we came up against the astonishing fact that he was no statesman, indeed that he had made every effort long before the war to destroy whatever remnants of German state structure he inherited, and that he replaced it by a chaos of 'states within the state'. Now, in Hitler's ideology, we find the theoretical justification for this blunder. Hitler was not interested in the state, did not understand the state, and actually did not think much of it. He was concerned only with nations and races, not with states. The state to him was 'only a means to an end', the end, in brief, being the waging of war. Consequently Hider did not omit anything during the years 1933-39 with regard to war preparations, but what he created was a war machine not a state. And for that he had to pay dearly.

A state is not only a war machine - at most, it may possess one — nor is it necessarily the political organization of a nation. The idea of the national state is no older than two hundred years. Most states in history comprised, or still comprise, many nations, such as the great empires of antiquity, or indeed the present-day Soviet Union; or else they comprised only portions of a nation, such as the city states of antiquity and the present-day German states. For all that they do not cease to be states, nor do they cease to be necessary. The idea of the state is much older than the national idea; and states do not exist principally for the purpose of waging wars, but, on the contrary, for the preservation and safeguarding of the external and domestic peace of their inhabitants, no matter whether these are nationally homogeneous or not. States are systems of order. War, no less than civil war, is for them an exceptional emergency; in order to cope with such emergencies, states have their monopoly of power, their armed forces and their police, but they do not have it in order to conquer living space for one nation at the expense of other nations, or for waging wars to improve the race, or to attain world domination.

None of this was known to Hitler — or perhaps one should say: he did not want to know about it. For there is no denying the voluntarist trait in Hitler's view of the world: he saw the world as he wanted to see it. That the world is imperfect, full of conflict, hardship and suffering, including the world of states which is riddled with mistrust, fear and war - this is only too true, and it is quite right not to shut one's eyes to it. So long as he says no more than that, Hider stands firmly on the ground of truth. Except that he does not state these things with the sad courageous earnestness with which Luther calmly faced what he called original sin, or Bismarck what he called earthly imperfection, but with that frenzied voice with which Nietzsche, for instance, so often hailed what was deplorable. To Hitler the emergency was the norm, the state was there in order to wage war. And that is where he was wrong. The world is not like that, not even the world of states. In the world of states, such as it is, wars are invariably waged for peace; and not only defensive wars but also aggressive wars if they have any meaning at all. Every war ends with a peace treaty or a state treaty and, hence, with a new state of peace which as a rule persists much longer than the state of war which preceded it. Once the military decision has taken place peace must be concluded, or else the war would have been pointless.

From Survival in Auschwitz & The Reawakening, by Primo Levi(*****): 2. Did the Germans know what was happening?

How is it possible that the extermination of millions of human beings could have been carried out in the heart of Europe without anyone's knowledge?

The world in which we Westerners live has grave faults and dangers, but when compared to the countries in which democracy is smothered, and to the times during which it has been smothered, our world has a tremendous advantage: everyone can know everything about everything. Information today is the "fourth estate": at least in theory the reporter, the journalist and the news photographer have free access everywhere; nobody has the right to stop them or send them away. Everything is easy: if you wish you can receive radio or television broadcasts from your own country or from any other country. You can go to the newsstand and choose the newspaper you prefer, national or foreign, of any political tendency—even that of a country with which your country is at odds. You can buy and read any books you want and usually do not risk being incriminated for "antinational activity" or bring down on your house a search by the political police. Certainly it is not easy to avoid all biases, but at least you can pick the bias you prefer.

In an authoritarian state it is not like this. There is only one Truth, proclaimed from above; the newspapers are all alike, they all repeat the same one Truth. So do the radio stations, and you cannot listen to those of other countries. In the first place, since this is a crime, you risk ending up in prison. In the second place, the radio stations in your country send out jamming signals, on the appropriate wavelengths, that superimpose themselves on the foreign messages and prevent your hearing them. As for books, only those that please the State are published and translated. You must seek any others on the outside and introduce them into your country at your own risk because they are considered more dangerous than drugs and explosives, and if they are found in your possession at the border, they are confiscated and you are punished. Books not in favor, or no longer in favor, are burned in public bonfires in town squares. This went on in Italy between 1924 and 1945; it went on in National Socialist Germany; it is going on right now in many countries, among which it is sad to have to number the Soviet Union, which fought heroically against Fascism. In an authoritarian State it is considered permissible to alter the truth; to rewrite history retrospectively; to distort the news, suppress the true, add the false. Propaganda is substituted for information. In fact, in such a country you are not a citizen possessor of rights but a subject, and as such you owe to the State (and to the dictator who represents it) fanatical loyalty and supine obedience.

It is clear that under these conditions it becomes possible (though not always easy; it is never easy to deeply violate human nature) to erase great chunks of reality. In Fascist Italy the undertaking to assassinate the Socialist deputy Matteotti was quite successful, and after a few months it was locked in silence. Hitler and his Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, showed themselves to be far superior to Mussolini at this work of controlling and masking truth. However, it was not possible to hide the existence of the enormous concentration camp apparatus from the German people. What's more, it was not (from the Nazi point of view) even desirable. Creating and maintaining an atmosphere of undefined terror in the country was part of the aims of Nazism.

It was just as well for the people to know that opposing Hitler was extremely dangerous. In fact, hundreds of thousands of Germans were confined in the camps from the very first months of Nazism: Communists, Social Democrats, Liberals, Jews, Protestants, Catholics; the whole country knew it and knew that in the camps people were suffering and dying.

Nevertheless, it is true that the great mass of Germans remained unaware of the most atrocious details of what happened later on in the camps: the methodical industrialized extermination on a scale of millions, the gas chambers, the cremation furnaces, the vile despoiling of corpses, all this was not supposed to be known, and in effect few did know it up to the end of the war. Among other precautions, in order to keep the secret, in official language only cautious and cynical euphemisms were employed: one did not write "extermination" but "final solution," not "deportation" but "transfer," not "killing by gas" but "special treatment," and so on. Not without reason, Hitler feared that this horrendous news, if it were divulged, would compromise the blind faith which the country had in him, as well as the morale of the fighting troops. Besides, it would have become known to the Allies and would have been exploited as propaganda material. This actually did happen but because of their very enormity, the horrors of the camps, described many times by the Allied radio, were not generally believed.

The most convincing summing-up of the German situation at that time that I have found is in the book DER SS STAAT (The Theory and Practice of Hell) by Eugene Kogon, a former Buchenwald prisoner, later Professor of Political Science at the niversity of Munich:

What did the Germans know about the concentration camps? Outside the concrete fact of their existence, almost nothing. Even today they know little. Indubitably, the method of rigorously keeping the details of the terrorist system secret, thereby making the anguish undefined, and hence that much more profound, proved very efficacious. As I have said elsewhere, even many Gestapo functionaries did not know what was happening in the camps to which they were sending prisoners. The greater majority of the prisoners themselves had a very imprecise idea of how their camps functioned and of the methods employed there. How could the German people have known? Anyone who entered the camps found himself confronted by an unfathomable universe, totally new to him. This is the best demonstration of the power and efficacy of secrecy.

And yet. . . and yet, there wasn't even one German who did not know of the camps' existence or who believed they were sanatoriums. There were very few Germans who did not have a relative or an acquaintance in a camp, or who did not know, at least, that such a one or such another had been sent to a camp. All the Germans had been witnesses to the multiform anti-Semitic barbarity. Millions of them had been present—with indifference or with curiosity, with contempt or with downright malign joy—at the burning of synagogues or humiliation of Jews and Jewesses forced to kneel in the street mud. Many Germans knew from the foreign radio broadcasts, and a number had contact with prisoners who worked outside the camps. A good many Germans had had the experience of encountering miserable lines of prisoners in the streets or at the railroad stations. In a circular dated November 9, 1941, and addressed by the head of the Police and the Security Services to all . . . Police officials and to the camp commandants, one reads: "In particular, it must be noted that during the transfers on foot, for example from the station to the camp, a considerable number of prisoners collapse along the way, fainting or dying from exhaustion . . . It is impossible to keep the population from knowing about such happenings."

Not a single German could have been unaware of the fact that the prisons were full to overflowing, and that executions were taking place continually all over the country. Thousands of magistrates and police functionaries, lawyers, priests and social workers knew generically that the situation was very grave. Many businessmen who dealt with the camp SS men as suppliers, the industrialists who asked the administrative and economic offices of the SS for slave-laborers, the clerks in those offices, all knew perfectly well that many of the big firms were exploiting slave labor. Quite a few workers performed their tasks near concentration camps or actually inside them. Various university professors collaborated with the medical research centers instituted by Himmler, and various State doctors and doctors connected with private institutes collaborated with the professional murderers. A good many members of military aviation had been transferred to SS jurisdiction and must have known what went on there. Many high-ranking army officers knew about the mass murders of the Russian prisoners of war in the camps, and even more soldiers and members of the Military Police must have known exactly what terrifying horrors were being perpetrated in the camps, the ghettos, the cities, and the countryside's of the occupied Eastern territories. Can you say that even one of these statements is false?

In my opinion, none of these statements is false, but one other must be added to complete the picture: in spite of the varied possibilities for information, most Germans didn't know because they didn't want to know. Because, indeed, they wanted not to know. It is certainly true that State terrorism is a very strong weapon, very difficult to resist. But it is also true that the German people, as a whole, did not even try to resist. In Hitler's Germany a particular code was widespread: those who knew did not talk; those who did not know did not ask questions; those who did ask questions received no answers. In this way the typical German citizen won and defended his ignorance, which seemed to him sufficient justification of his adherence to Nazism. Shutting his mouth, his eyes and his ears, he built for himself the illusion of not knowing, hence not being an accomplice to the things taking place in front of his very door.

Knowing and making things known was one way (basically then not all that dangerous) of keeping one's distance from Nazism. I think the German people, on the whole, did not seek this recourse, and I hold them fully culpable of this deliberate omission.

From Justice at Nuremberg, by Robert E. Conot(***): The final arguments of the defense attorneys were notable for their prolixity, reams of irrelevancies, and plethora of banalities. Though the lawyers protested that the fourteen court days allotted by the tribunal were not enough, if measured by content four would have been too many.

Stahmer and Kauffmann, the counsel for Goering and Kaltenbrunner, both soared into the metaphysical. When Kauffmann went on and on about "surging waves of a furious torrent" and "demoniacal depths [in] which lurk those who hate the true God," Lawrence, after listening at length, finally suggested: "Is it not time that you came to the case of the defendant that you represent? The tribunal proposes, as far as it can, to decide the cases which it has to decide in accordance with law and not with the sort of very general, very vague and misty philosophical doctrine with which you appear to be dealing."

A number of the attorneys pleaded for leniency by depreciating their clients. Thoma thought Rosenberg had exaggerated his importance because "he does not want to be pictured as though nobody paid any attention to his books, his speeches, and his publications."

Marx suggested that Streicher "was a fanatic" who suffered from "a sort of mental cramp." Sauter called Funk "a topic which unfortunately is especially dry and prosaic." Siemers sanctimoniously proffered: "Raeder cannot be a criminal, since all his life he has lived honorably and as a Christian. A man who believes in God does not commit crimes, and a soldier who believes in God not a war criminal."

Servatius, continuing his inept conduct of Sauckel's case, maintained that his client was misunderstood. When Sauckel had advocated that "one should handcuff the workers in a polite way," Servatius argued, "the point in question was merely a comparison between the clumsy manner of the police and the obliging manner of the French; handcuffing was not thereby especially advocated as a method of mobilization: clean, correct, and Prussian on the one hand, while at the same time obliging and polite on the other; that is how the work was to have been done."

Since Speer's case followed Sauckel's throughout the trial, Flachsner, characterizing Speer as moderate and rational in contrast to the brutal Sauckel, stuck to his stratagem of seeking to exonerate Speer at Sauckel's expense. The prosecution could not have done a better job of undercutting Sauckel.

Kranzbuehler for Doenitz and Dix for Schacht maintained their reputations for skill and persuasiveness. Kranzbuehler emphasized the facts in favor of Doenitz, skirted around those that were detrimental, and manipulated analogy in subtle fashion. The fact that eighty-seven percent of the tailors from sunken ships had survived, Kranzbuehler argued, "is simply inn compatible with an order for destruction." If there had been isolated incidents in which men were attacked in the water, these had occurred on both sides. Referring to "cases in which Allied forces had allegedly shot at German shipwrecked crews," Kranzbiihler contended "that every one of these instances is better than that of the prosecution, and some appear rather convincing."

Dix painted a graphic picture of incongruity: "There in the dock sit Kaltenbrunner and Schacht. Whatever the powers of the defendant Kaltenbrunner may have been, he was in any case Chief of the Reich Security Main Office. Until those May days of 1945, Schacht was a prisoner of the Reich Security Main Office in various concentration camps. It is surely a rare and grotesque picture to see jailer and prisoner sharing a bench in the dock. The charge against him was high treason against the Hitler regime. Since the summer of 1944 I was assigned to defend Schacht before Adolf Hitler's People's Court; in the summer of 1945 I was asked to conduct his defense before the International Military Tribunal. This, too, is in itself a self-contradictory state of affairs. . . . No criminal charge whatsoever can be brought against Schacht personally. To the extent that he erred politically, he is in all candor prepared for the verdict of history. Yet even the greatest dynamics of international law cannot penalize political error."

Keitel's attorney, Otto Nelte, acknowledged Germany's responsibility, but pleaded for understanding:

"The misery, the misfortune that has fallen on the entire human race is so great that words do not suffice to express it. The German people, especially after having learned the catastrophes that have befallen the nations in the West and East and the Jews, is shaken by horror and pity for the victims. But while other nations are able to look upon all this misery and all this misfortune as a chapter of the past, there still rests upon this nation the gloom of despair. By affirming the guilt of the entire nation the verdict of this tribunal would perpetuate this despair. The German people does not expect to be acquitted. It does not expect the cloak of Christian charity and oblivion to be spread over all that has happened. The German nation is ready to the last to take the consequences upon itself. It hopes, however, that the soul and heart of the rest of mankind will not be so hardened that the existing tension, in fact the existing hatred, between this nation and the rest of mankind will remain."

From The European Powers 1900-45, by Martin Gilbert(****): Russia had mobilized with greater ease than was expected. Her cumbersome armies advanced with zest and on 17 August the northern army, commanded by General Rennenkampf, and the southern army under General Samsonov, both crossed into East Prussia. On 20 August Rennenkampf's army met the Germans at Gumbinnen. The Germans fled in panic, leaving 6,000 of their soldiers prisoners. The German commander was at once dismissed. His successor was a retired general of sixty-seven, not perhaps an auspicious choice. This retired general, Paul von Hindenburg by name, was given as his staff officer the man who had just distinguished himself at the caprture of Liege in the west, General Ludendorff. These two were on their way to the front by train when a plan, devised for the emergency of defeat, was put into operation on the initiative of Lieutenant Colonel Max Hoffman. Hindenburg and Ludendorff duly approved this plan. The Germans retreated in two directions, west by rail and southwest on foot. The rail movement turned south at Elbing, and at the neatest point to the Russian southern army the troops detrained. The spot at which it was decided to meet Samsonov's army was a hill called Tannenberg.

At first the Germans were at a strong disadvantage. The troops who had been moving southeast on foot had only reached Bischofstein. For two days Samsonov held the advantage. But what he might have gained by military skill was lost by technical folly. The Russians, not planning for the possibility of their own rapid advance, had neglected their communications system. Their telegraph facilities were inadequate and messages passed from front to rear with dignified sloth. At the same time they neglected to use code.

Their messages passed undisguised. The German wireless station at Konigsberg listened to the discussions of the Russian plan of campaign. What they heard was comforting. It appeared that Rennenkampf could not reach Gerdauen until 26 August, and was thus quite unable to come to Samsonov's assistance. At the same time the Russian wireless messages revealed that Samsonov himself did not regard the presence of German troops at Tannenberg as part of a concerted plan of attack. He thought that the army was an army in retreat. He thought that he had only to strike hard, follow closely, and thus drive the Germans to Danzig.

Samsonov was told of troops coming from Bischofstein but did not take alarm. Here, he argued, were more men in retreat, doubtless in hopeless disorder, flying from Rennenkampf's advance. He therefore dispatched a small force northwards to break the advancing rabble. But the troops with whom they were faced were marching towards battle, not away from it. They were determined to reach Tannenberg as quickly as possible and far outnumbered the men whom Samsonov had sent to crush them. Thus Samsonov's right flank was pierced. But such was the inadequacy of Russian communications that he did not learn of this in time to regroup his forces.

The Germans drove in from the north, passing Ortelsburg on 27 August. General Francois, commander of one of the German armies, ignored instructions from Ludendorff to turn north when he reached Neidenburg. Frangois decided on a more subtle tactic. He moved on to Willenberg. It was precisely across the Neidenburg-Willenberg line that the Russians could retreat. Now that line was denied them, thanks to the virtual disobedience of Ludendorff's subordinate. As the German Army from the north pressed beyond Ortelsburg and swung west Samsonov was surrounded. The Germans took 122,000 prisoners, of whom Frangois obtained over a half. Samsonov walked alone into the woods and shot himself.

The Russian attack was at an end. The Germans had a victory which was to remain a symbol of national revival for many generations. At Tannenberg the invading armies had been checked; at Tannenberg German honor had been saved. To whom did the laurels of this triumph go? A study of the battle shows that Max Hoffman devised the plan and that Francois enabled it to be carried out to maximum effect. In the heat of war other conclusions were reached, chief among them that Ludendorff was the victor of Tannenberg and that in combination with Hindenburg, his aging superior, he had marshaled the forces of Germany against the foe. For Frangois and Hoffman there was to be no such immediate fame.

From Hitler's Foreign Policy 1933-1939: The Road to World War II, by Gerhard L. Weinberg(****): Hitler would still prefer to split Britain and Poland but was determined to attack the latter even at the risk of a wider war. At the time when the German army, therefore, was in the last stages of a secret but full mobilization, which had begun on 26 August even though the attack order had been canceled, the Polish government was still being urged by the Western Powers to defer its mobilization lest the blame for the outbreak of war fall on Poland in any future discussion analogous to that about the sequence of mobilizations in 1914.

When Hitler received the British reply on 28 August, he quickly saw that the projected alliance had not had the effect of driving a wedge between England and Poland as he had hoped and that another approach would be needed for the same purpose. He would now utilize the British statement of Poland's readiness for direct German-Polish negotiations to demand the appearance of a Polish plenipotentiary in Berlin on 30 August, the day after so insisting to Sir Nevile Henderson. If the Poles refused to comply with this repetition of the procedure used with Hacha in March, Hitler could blame his subsequent attack on Poland on the intransigence of the latter and hope that in such a situation Poland would be isolated. If, however, a Polish plenipotentiary did appear in Berlin on 30 August as demanded, the Germans would toss on the table such demands as to assure a breakup of the negotiations on 31 August, with war starting on 1 September just the same and with all blame placed by German propaganda on the obstinacy of the Polish representative and government.

As Hitler put forth the demand for an immediate Polish surrender, the German propaganda machinery was attuned to the situation. The wild German press campaign against England was to be toned down and there were to be no personal attacks on Chamberlain. On the other hand, stories of Polish "atrocities" against Germans in Poland were to dominate the newspapers. Whether or not anybody inside or outside Germany believed in these atrocities was considered unimportant; the critical point was to play them up. While this was the German propaganda posture on 29 August, in the chancellery Hitler took the position among his advisers that he wanted a little war; that if the other powers joined in that would be their fault, but that in any case, a war was needed.

Hitler was not to be disappointed this time. Beck wanted peace; and whatever the Polish underassessment of German might, overassessment of their own strength, and overconfidence in the power of their French and British allies, there was a clear understanding of the danger to Poland if war came. But as the British ambassador to Poland, Sir Howard Kennard, commented on the scheme Hitler had given Henderson, "they would certainly sooner fight and perish than submit to such humiliation." Beck was not another Hacha or von Schuschnigg. On the other hand, if Hitler thought that his new tactic would in any way influence London to abandon Poland, he was totally mistaken.

On the contrary, the British government immediately let it be known in Berlin that the demand for the appearance of a Polish plenipotentiary in Berlin on 30 August was quite unreasonable in their eyes, and they implicitly conveyed the same opinion to Warsaw by being careful not even to inform Poland officially of this preposterous demand until after the 30 August deadline had already passed. The British government was all in favor of a negotiated settlement arrived at in a neutral location by talks in a calm atmosphere and without threats of war; they were careful to urge both the Germans and the Poles to pursue such a course, but they would not badger the Poles into concessions as Henderson, for example, was urging.

On 30 August, the day on which Hitler expected that either there would be a Polish negotiator to be confronted with impossible demands or, lacking that, a split between England and Poland, he set the schedule for the beginning of war. As already tentatively fixed on 28 August, the attack on Poland was now scheduled for the early morning of 1 September. If the talks with London made a further postponement necessary, the attack could be shifted to 2 September; the army would be informed by 3:00 p.m. on the 31st if the situation called for another day's wait. After 2 September the planned attack would have had to be canceled altogether.

Very revealing, and sometimes overlooked in the literature on the subject, is the fact not only that Hitler held to the 1 September date rather than allow the additional day of negotiations his own schedule permitted but that in the event he could see no reason even to await his 3:00 p.m. deadline on the 31st. The order to attack on 1 September reached the high command of the German army by 6:30 a.m. on 31 August, and by 11:30 a.m. it was also known there that Hitler had decided to attack although intervention of the Western Powers probably could not be avoided. War, even a general war, in other words was not the last resort when all avenues for negotiations had been explored to the last minute, but was rather perceived by Hitler as the desired procedure to be adopted at the earliest moment circumstances seemed to allow.

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies

Featured Sites:

Disclaimer: The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Fair Use Notice: The Propagander!™may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies